Tuberculosis (TB) is the leading cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide (excluding COVID-19), infecting about 10 million people every year. The clinical syndrome is caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which creates its own reservoir by lying latent after resolution of the primary infection so it can re-infect the host and cause more severe disease. In 2017, one research team estimated that 24% of the global population were latently infected, despite prevention protocols, diagnostic tools and treatments1.

The World Health Organization is aiming to reduce tuberculosis incidence by 10% a year by 2025; currently, the rate of decline is around 2%1. The 10% goal was based on historical data from the fifties and sixties in Western Europe, where infection was controlled by thorough prevention, diagnosis and treatment of efforts of all forms of TB, as well as by expanding healthcare coverage and welfare programs that improved socioeconomic hardships such as poor living conditions and nutrition. These efforts in London, Wales, and the Netherlands led to a significant reduction in the incidence of TB and TB-related mortality2. Interestingly, Cape Town adopted similar measures to control the spread of TB in the early 2000s, but saw less of a reduction in incidence, likely because of lack of efforts to change the social determinants of health. These contrasting results show that improving socioeconomic status for people living in high-burden places is just as important as public health measures that directly slow the spread of disease1.

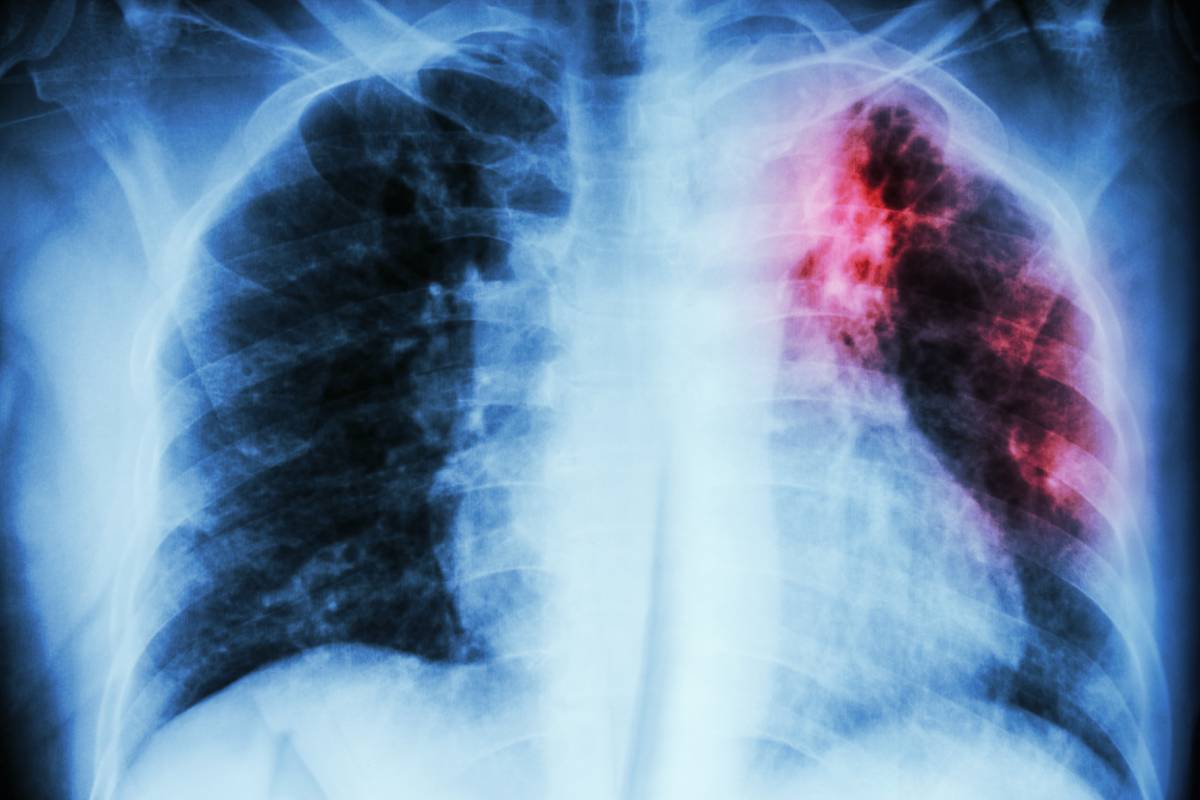

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is spread in five steps. First, an individual with an active infection of TB aerosolizes the bacteria living in their lungs, by breathing, talking, shouting, singing, etc. The bacteria can survive in the air for a time, before it is breathed in by someone else who is not currently infected. Bacteria then goes to the lungs, typically the middle or lower lobes, and causes primary infection. Once the primary infection has resolved, it lies latent in calcifications in the lungs until it is reactivated by immunosuppression or other host factors1.

Not all hosts are equally infectious, and infectivity depends on many host-related and bacterial factors. For example, people with smear-positive pulmonary TB were more likely to spread it to their household and close contacts than those with smear-negative cases. Patients with HIV or otherwise similarly immunosuppressed patients were less likely than immunocompetent patients to spread the disease1. Unsurprisingly, household contacts are the most likely to get sick, and this effect is amplified in countries that also have a high burden of HIV. And finally, access and adherence to antiretroviral therapy is protective against TB infection in patients with HIV, despite this patient population being particularly vulnerable. Since much of this evidence links TB with HIV, it may be advantageous to improve access to medication, prophylaxis and diagnostic tests to HIV as well as TB2.

First-line treatment of active, drug-susceptible TB consists of a four-drug regimen: rifampin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. These must be taken for six to nine months to resolve infection, and each drug carries its own adverse effects and toxicities. Furthermore, as TB spreads, the risk of multi-drug resistant TB also increases, and that is much more complicated to treat. Due to the major morbidity and mortality caused by TB, as well as the complexity of treatment, reducing the incidence of TB is a leading public health problem3. Evidence shows that the best way to do this not only to expand prevention protocols and access to TB specific healthcare, but also to improve socioeconomic risk factors and HIV prevalence.

References

- Churchyard G, Kim P, Shah SS, Rustomjee R, Gandhi N, Mathema B, Dowdy D, Kasmar A, and Cardenas A. What We Know About Tuberculosis Transmission: An Overview. The Journal of Infectious Disease, 2017; 216: S629-S635. https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jix362

- Lienhard C, Glaziou P, Uplekar M, Lonnroth K, Getahun H, Ravliglione M. Global tuberculosis control: lessons learnt and future prospects. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2012; 10: 407-416. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro2797

- Nahid P, Dorman SE, Alipanah N, Barry PM et al. Executive Summary: Official American Thoracic Society/CDC/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosis. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2016; 63(7)L 853-867. https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciw566